For visual interpreters of the world like me, having the time to concentrate on finding and interpreting historic original materials is both essential and precious. Being a participant in the Jay and Deborah Last Visiting Fellowship for Creative Artists from the American Antiquarian Society (2016) boosted both my curiosity and confidence as a professional artist. Searching for original objects within the space of the reading dome became for me a kind of ritual for me, one that was both deeply joyous, layered as it was in history and tradition, and hugely transformational in terms of my process of making art. Years from now I will remember and reference that unique time of discovery with immense gratitude and a kind of awe.

Lapie, M. Pierre (1806). Reproduced courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Reproduced courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

I first learned about the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) in the spring of 2015 over a margarita and chicken tacos at La Choza, a favorite restaurant in my hometown of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Writer and cultural historian Phillip F. Gura was visiting a mutual friend, and we were celebrating the recent publication of Gura’s history of AAS from 1812-2012. Phillip encouraged me to apply for the AAS Creative Fellowship, and I did! A year later I found myself in Worcester, Massachusetts, immersed in the enormous AAS archive, looking for maps and other ephemeral materials that would aid in my interpretation of the landscapes during John James Audubon’s time (1750-1860).

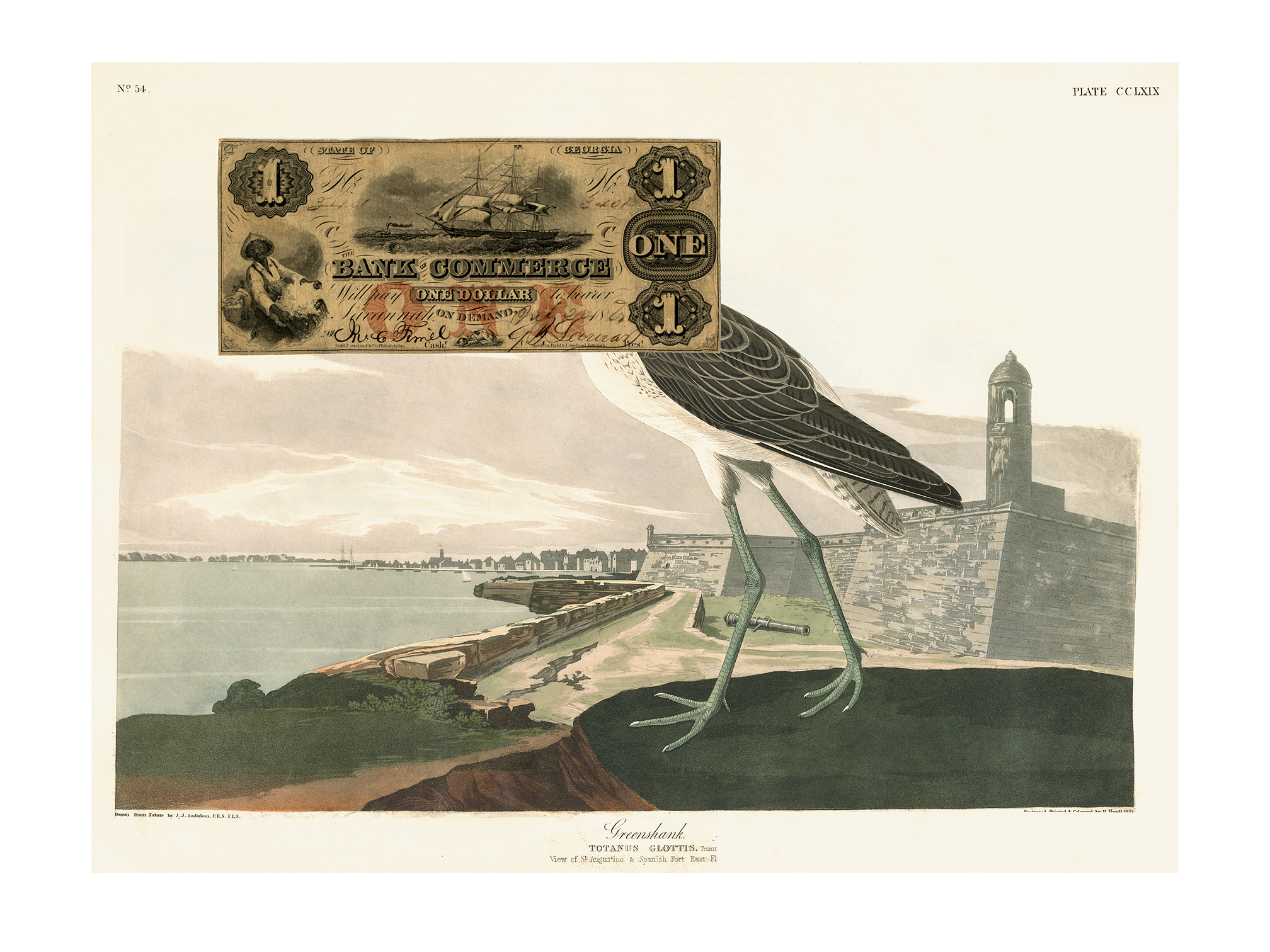

What I like to call “going down the rabbit-hole” was, thankfully, right in line with the style of research inquiry that AAS promoted to all the entering Fellows. Thanks to their encouragement and help pointing me in numerous intriguing and unexpected directions, I stumbled onto multiple boxes of early nineteenth-century banknotes. Along with the maps, these banknotes proved invaluable to my understanding not only of the landscapes and economies of Audubon’s time, they inspired many of the collages featured in my forthcoming book, A Country No More: Rediscovering the Landscapes of John James Audubon (George F. Thompson, June 2021). Both the collages and certain individual maps provide an invaluable guide to viewers and readers, allowing them to make important connections between Audubon’s peregrinations, and their historical context.

Collage Insets: A Map of the United States and British provinces of Upper and Lower Canada with other parts adjacent (New Haven, CT: Shelton and Kensett, 1816). Map and banknotes reproduced courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

Several of the maps I saw from the period between 1750 and 1860 were so large that they required two or three staff members to bring them out for me to look at. The process of carefully unfolding/folding them for viewing, was both tactile and transforming. As objects, each one of them has survived long journeys over more than two centuries. They wear their stories on their surfaces. Discovering the early nineteenth-century banknotes, which, along with the period maps, proved to be surprisingly excellent guides to my journey through the heartland of America, allowed me to understand in a way I had not previously the changes that have occurred there between those times and our own.

Krista Elrick (September 23, 2010), 4:00–7:00 p.m. Medium: Silver-gelatin collage, archival pigment-ink collage.

Krista Elrick (October 2012). Medium: Silver-gelatin film, archival pigment-ink collage.

Krista Elrick (February 17, 2010). Medium: Silver-gelatin film, archival pigment-ink collage.

My fellowship experience reminds me why Audubon insisted that his Birds of America prints were, “Drawn from Nature” in “Actual-Size.” His demand for working with original sources was uncompromising. He lived and worked inside the avian habitat. He hunted down his own subjects, and then painted them while they were dying. Afterwards he stuffed them for the edification of future generations. I too feel that the original resources in the AAS collection were integral to my creative process. Making collages with historical documents is new to me, although the process of searching for the materials is similar to my search with cameras. Constructing my collages begins on a large sheet of paper, where I layer unexpected materials together in order to create a narrative dialog.

Krista Elrick (October 2012). Medium: Silver-gelatin film, archival pigment-ink collage.

As a photographer, I too require being in the presence of real things in real physical places in order to make my work. Protected inside my large and medium format cameras, the black and white film frames and collects the original light. Once exposed, the film renders my view into a two dimensional plane. All of which is done during a very specific moment in time, and, in the place where I occupy. I develop my exposed negatives in a darkroom. Once finished, my silver gelatin prints and collages are sequenced and installed into contemplative spaces, such as exhibition walls and creatively designed portfolios and books.

Krista Elrick (2020). Collage Insets: Common Greenshank (Tringa nebularia), Havell Plate No. 269. Drawn from Nature and Published by John J. Audubon, F.R.S. F.L.S. / M.W.S. Plate 269; vol. IV. The Elephant Folio Engravings of, The Birds of America, 1835–1838. Robert Havell, Jr., Engraver; Watercolor and aquatint applied by anonymous colorists in London, England. Reproduced courtesy of the National Audubon Society, New York City. Banknotes reproduced courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.